These stories are inspired by the 100 Days project film clips of John Timmons’ (corresponding clips are linked below each title) and each is in response to his own daily piece or that of one of the other participants.

Note: only the most current stories are accessible, to secure the text and particularly, the images from being nabbed by and displayed on public sites. If you would like to read some of the stories that are here, simply email me at smgct1@comcast.net for the password.

*****

#50 THE HOLE

(hole)

It was a secret that no one knew but Grenadine. It was a hole in the ceiling just above her bed that appeared overnight though she didn’t hear anything happening. There was plaster dust in her bed when she awoke and she looked up and saw a hole about the size of a grapefruit. She covered it with a poster of Justin Timberlake and went to school.

It was a secret that no one knew but Grenadine. It was a hole in the ceiling just above her bed that appeared overnight though she didn’t hear anything happening. There was plaster dust in her bed when she awoke and she looked up and saw a hole about the size of a grapefruit. She covered it with a poster of Justin Timberlake and went to school.

Grenadine had always wished she could fly. She dreamed of swooping out the window into the black night speckled with stars. She’d peek into that mean, stuck-up Carolina Cavendish’s bedroom and maybe steal some of her clothes. She’d peek into Justin’s window and maybe steal a kiss. Or maybe just lay there cuddled next to him until he woke and found her and made mad passionate love to her and asked her to marry him. Her mother called Grenadine a dreamer. “Dreamers dream, honey,” she’d say, “but doers do.” Grenadine thought that was an idiotic thing to say.

The first time she put something up into the hole was an accident. It was a can of black olives she’d taken from the pantry and hidden under her bed to enjoy all by herself, the whole can, at night. Sometimes she did that with canned tiny shrimp. She was halfway through the olives, reading War and Peace, when her door opened and her mother started to come in. Grenadine threw the can up into the hole and taped Justin back in place.

“Grenadine, stop jumping on the bed!” said her mother.

“Mother, I’ve asked you to please knock before you come in!” said Grenadine.

Asleep, Grenadine would send her nightmares into the hole so that she could spend more time with her dreams. She also put in the green blouse she hated, her eleven year-old brother’s favorite Zoid, last evening’s broccoli, an angora sweater she had ‘borrowed’ from Carolina, her mid-term report card, an occasional peanut butter sandwich, and all the stuff she couldn’t jam into the closet or under the bed when her mother made her clean up her room.

She stuck the Anderson’s cat who hunted the birdfeeder up into the hole, and eventually the Gerelick’s loud barking dog. She was surprised at the hole’s capacity to fit everything through it. Out of curiosity, she came home with an elephant one Saturday afternoon when everyone else was away.

“Damn,” she said in amazement, as she stuffed the last gray bit of him through. Then Grenadine got an idea.

“Hey, Carolina!” she called, spotting Carolina in the hall between bells. “Carolina, wait up!”

Carolina stopped and turned around, rolled her eyes at her friends. “What, twirp?”

“Carolina, I think I found your pink sweater. I think it was under my jacket at the party Saturday night and I must’ve taken it with me by mistake,” Grenadine said.

“You weren’t at the party,” said Carolina. “You weren’t invited.”

“Yes, I was. I was there. There were just so many people you probably didn’t see me. Great party.”

“Well, so give it back then.”

“It’s at my house. You can come pick it up after school.”

“Just bring it in.”

“Well, that wouldn’t be until next Tuesday. Monday’s a holiday, remember?”

Carolina tsked in annoyance. “Oh all right. Where do you live?” she exhaled in a loud sigh.

“Three doors down from you,” Grenadine smiled. “The blue house. Number 33.”

When Carolina came over, Grenadine made her come upstairs to her bedroom. “Listen to this,” she said. She clicked on Justin’s latest recording.

“Where’s my sweater?” said Carolina.

“I’ll get it in a minute,” Grenadine replied. She sat cross-legged on the bed. She threw a handful of peanuts up into the hole. “Isn’t he great?” she said, half-closing her eyes and swaying to the song. She tossed up another handful of peanuts into the hole.

Carolina at first had watched with disinterest. She scrunched up her face and finally asked, “What are you doing?”

“There’s an elephant up there,” said Grenadine, “and he’s hungry.”

Carolina snorted. “Yeah, right. I’m in a hurry, where’s my sweater?”

Grenadine smiled and pointed up at the hole.

“Moron!” said Carolina in disgust. She got up on the bed, shoes and all, stood up and reached up towards the hole. “Freakin’ idiot,” she muttered as she started to jump up and down so she could reach. Up and down, up and down, up and up she went.

“You’ll have to fight the elephant for the peanuts,” Grenadine said, as she threw the whole bag through the hole and taped Justin back in place.

*****

#49 SCRATCH

Her nails dug in to find the sweet spot. Emma sighed in relief. Psoriasis was a plague from God; scratching was bliss.

It had started to itch when she stood at the bus stop, loaded down with her purse and a shopping bag in each hand. Around her, a small crowd gathered to wait. She got on and went to the back bench of the bus. Three more people sat down on the seat. It was impossible to scratch without attracting attention. She had tried rubbing her forearm against her waist and accidentally bumped the man sitting next to her who had half-smiled at her mumbled apology but he was looking down at her arms. He inched away, like a puddle evaporating in the sun.

She thought of her day at the office but that did not take her mind off the itch and made her feel bad as well. Emma’s stop was one of the last on the line. She looked up and reread advertisements and waited through stops. There were only a few people staring out windows or down at their laps, engrossed in a book or knitting a sweater for someone’s new baby. She now sat alone on the bench. She looked around and caught the driver watching in the rearview mirror.

She thought of her day at the office but that did not take her mind off the itch and made her feel bad as well. Emma’s stop was one of the last on the line. She looked up and reread advertisements and waited through stops. There were only a few people staring out windows or down at their laps, engrossed in a book or knitting a sweater for someone’s new baby. She now sat alone on the bench. She looked around and caught the driver watching in the rearview mirror.

It started to itch madly, a tiny spider out exploring her arm. She tentatively fingered the area, unable any longer to ignore it. Lightly, very lightly, she drew her nails along the perimeter, on the outer edge, on the skin still unreached by the growing island of thick pink scale. Back and forth with little pressure, like an intimidated lover hopeful yet ever circling the edges of self-doubt. Scales of skin fell to the floor. She spread them around with her foot.

On the next stop, a young woman got on, holding the hand of a small boy she maneuvered ahead of her. They came all the way down the aisle, the boy’s eyes wide in adventure, his mouth open in that small sense of fear. He focused on Emma sitting by herself on the bench at the back of the bus. He liked the bench. He liked to crawl on it, lay down on it, climb down and back up. But the lady was there, in the very middle of it. She was absently scratching her arm.

The young woman was guiding the boy around Emma’s packages when she stopped and pulled him back. Emma looked up and caught the woman’s eye for a heartbeat before the woman looked away. She led the boy to a seat a few rows from the back, shushing his whining with mumbled words that Emma could almost not hear. Her face turned psoriasis pink. Her hands dropped into her lap. She wrapped her fingers around the shopping bag handles and when she looked up, the boy was right there. His mother called his name loudly. Emma smiled at him. He stuck out his tongue at her then spun around and ran back to his seat.

She started to rise as the bus slowed, almost lost her footing as it jerked to a stop. As she passed the seat where the boy sat with his mother she brushed her arm in a shower of flakes and whispered, “fairy dust” to the boy’s upturned face. The mother looked up, but a split second too late as Emma stepped down and got off.

She put the bags down on the sidewalk, elbowed her purse, watched the bus pull away, and scratched.

*****

#48 WAITING

(the act of changing location)

Because he was nervous he’d arrived early. Because he was early, he was nervous. In the terminal people streamed by, rushing toward him, coming up from behind in a lava flow, opening and closing around him. It was hard to breath. He wished she’d taken an earlier train, out of time with commuters. He got clipped by a woman who zipped by in a motorized chair who looked back at him with one eye and grinned.

Because he was nervous he’d arrived early. Because he was early, he was nervous. In the terminal people streamed by, rushing toward him, coming up from behind in a lava flow, opening and closing around him. It was hard to breath. He wished she’d taken an earlier train, out of time with commuters. He got clipped by a woman who zipped by in a motorized chair who looked back at him with one eye and grinned.

He went down into the tunnels, stood on the platform well back from the tracks. There were many people but they gathered in clots, coming down the stairs and taking a spot where they stood, immobile, reading newspapers and texting or talking on phones. He wondered what she would look like, if the years had changed her at all. He looked at his watch. Her train wasn’t due in for at least a half hour. Even so, as he heard the approach of the subway he moved with the crowd.

The same mass of people who stepped off the train were replaced by those who got on. The doors whooshed shut and the train started up. A man who’d been standing beside him now ran through the cars from the front to the back at the same speed as the train pulled forward. The man waved a machete over his head. No one else, on the train or the platform, appeared to notice. For a few seconds the man on the train was running in place with the man waiting on the platform. Then the train picked up speed and was gone.

He looked around but no one seemed to have seen it. He noticed that there were just as many people there as before. He looked down and saw hundreds of feet, all paired up in shoes. Another train was approaching and again he moved up with the others, looked up and watched as it flew towards them. It flew by. All he saw was the rush of faces and hands pressed up against windows, a blur of expressions between laughter and fear. Flat noses, wide eyes, huge mouthfuls of teeth. Fingers clawing at glass.

Now there were twice as many people as before. He couldn’t turn around. He felt the drop-off edge of the platform midway under his feet. He looked down and saw thousands of shoes. He was sweating but couldn’t reach up to wipe it away.

It happened twice more. The crowd pressed upon his back. He felt their breathing in sync and the tunnel expanded with each inhalation and deflated in a mob-run exhale of warm air. The trail of overhead lights flickered and hummed.

When he looked down, he could not see his own feet in the matched sets planted around him. When he looked up, she was suddenly there.

*****

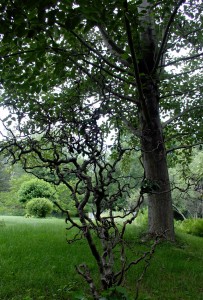

#47 TWO TREES

“Wishes are for the witless,” the old man would say and, “dreams are for fools.”

“Wishes are for the witless,” the old man would say and, “dreams are for fools.”

He was cranky and sharp as the blade of an arrow. He was tall and skinny and looked hard and mean. He was the most intelligent man I’ve ever known. He was my father’s father, outliving his wife and his friends and my father as well. He kept himself busy creating new things every day.

He’d come to this country as a young man, full of ideas and ambition. From what my grandmother said, he had no money, but a great way with words and what struck her was his blunt honesty. When he told her she was pretty, she could believe him. When he said that he loved her, she married him without thinking twice.

In their back yard they had a fine garden that bloomed with all sorts of flowers and dahlias as big as your head. Their vegetables were the most abundant around. But my grandfather pulled me away from picking beans one day–I was probably around eight–and brought me over to a huge cottonwood tree that stood towering over the house.

He pointed up to the top where leaves clawed at the sky. “I planted this twenty years ago,” he said, “and it was less than half the size of you.”

I looked up in awe, never having thought that something could grow so tall in that time. Twenty years was like, well, two and a half times as old as I was.

“See how straight it grows, reaching out its branches, reaching up. It must’ve grown five to six feet or more every year. Never fed it anything special. One year it broke nearly in half but it just took a different path and formed a new center.”

“Wow, Grandpa! It must be very strong.”

“Determined. Focused. Independent. Flexible, that’s what it is, boy,” he said. With one hand on my shoulder he turned my attention to a small gnarl of branches that was just about the same height as me. “That’s a Filbert Tree,” he said, “also called a Walking Stick. It was planted the very same year.”

I remember thinking how cool the little tree looked. Each limb garbled and twisted like snakes. A handful of leaves clung to it, like clouds caught on its branches.

“The Filbert has spent most of its lifetime in dreams of what it wanted to be, where it wanted to reach,” the old man said. “It listened to this wind or that one, it’s eye captured by the North Wind, then the South. It wanted, it wanted, but it reached out for help instead of depending on its own sturdy stock. It never knew enough to simply reach for the sun in the sky and grow.”

“But isn’t it good to have dreams?” I’d asked him.

“Dreamers have dreams, but the smart folk have plans,” he said. “Would you rather a drawer full of dreams or a pocket full of accomplishments?”

That was years ago; I’m now thirty-two. My life has exceeded my own expectations–not dreams, expectations. My grandfather is gone now, but the cottonwood still pierces the sky with bravado, and the filbert still clings to its precious few leaves.

*****

#46 FAMILY PORTRAIT

(posing)

The portrait hung as both history and obituary to the Gresyk family line. Adrienne could point to each one and name off their DOB and DOD as each peeled away like corn husks from the core of her life, leaving behind only a bit of themselves in Adrienne. Great Grandfather’s height, Aunt Ethel’s chubby upper arms, her mother’s pug nose, her father’s dark eyes, all pieces and parts that made her what she was. She stared at the image of a gathering of half-smiling people, glad they were all safely locked behind glass.

The portrait hung as both history and obituary to the Gresyk family line. Adrienne could point to each one and name off their DOB and DOD as each peeled away like corn husks from the core of her life, leaving behind only a bit of themselves in Adrienne. Great Grandfather’s height, Aunt Ethel’s chubby upper arms, her mother’s pug nose, her father’s dark eyes, all pieces and parts that made her what she was. She stared at the image of a gathering of half-smiling people, glad they were all safely locked behind glass.

Adrienne’s home was a collage of old memories. Prom corsages pinned to the walls, kept fresh and ever-blooming with a mist of orange juice and milk every morning. A worm that brought in her first rainbow trout. The trout itself on a plaque. And the boy who had taken her fishing, posed in an angling position, with his arms up and casting. She’d baited his hook with a waterbug.

“You’re a hoarder,” her sister had said when Adrienne had first moved away from home into an apartment in the city. There were paths cut through the rooms with velvet rolled guides strung on heavy brass stands, like in a museum or a movie theater to prevent sneaking in without paying. “One should walk slowly, savor each step,” Adrienne said. There was so much to see. Eventually she bought an old house on a nice quiet street and quit her job at the clinic. Decorating was more than a hobby; it took up all of her days.

For the things she had lost, thrown away without thinking, there was e-bay. For the people who were beyond her reach she used mannikins carefully clothed in the right style of the day (here, the thrift shops were a huge help) and fixed with the hair colors and styles she remembered. It made her feel alive in the middle of the crowd, it gave her life purpose.

Eventually it was more than Adrienne could handle as her age overcame her enthusiasm. It broke her heart to see the rose nosegays and the special gardenia wristlet shrivel and die. Andy the angler fell over in the dead of night and she had to leave him there, face down on the floor. When she became ill with diphtheria (she suspected she also contracted on ebay), she never fully recovered and one Sunday morning, as church bells rang off in the distance, Adrienne died.

Several weeks later they found her, dry and brittle, sitting in the one chair in the house. The other five pieces of furniture were hauled off by the town crew on large trash pickup day. The bare walls were painted in ivory to set off the wonderfully warm woodwork and the house was put on the market for back taxes owed. Adrienne was buried in the pauper’s corner of St. Mary Magdalene’s Cemetery and the family portrait that had hung all by itself on the living room wall was taken out of its frame and someone reused the frame for a mirror.

*****

#45 LIFE MELTING

(flow)

You can’t blame me; I didn’t see it. God knows it’s tough enough to survive each day much less make it in this world. I had a family, a home, ambition. I didn’t think I was being single-minded but rather, focused. I’ve worked hard to get here. I’ve innovated and I’ve rolled with the punches. Gone with the flow and swam against it. Whatever I had to do I did.

You can’t blame me; I didn’t see it. God knows it’s tough enough to survive each day much less make it in this world. I had a family, a home, ambition. I didn’t think I was being single-minded but rather, focused. I’ve worked hard to get here. I’ve innovated and I’ve rolled with the punches. Gone with the flow and swam against it. Whatever I had to do I did.

John Smith is forty-six years old. He is a Vice President of Operations at Gem Oil Corporation. It is an American company but headquarters are based in Tokyo where he has moved his family for a contracted period of three years. It has been five already. He is on a business trip to the Pittsburgh, PA office, where the staff has dieted down to a skeleton. His presence there could only mean one thing: the Pittsburgh, PA office will be closed.

They look at me strangely, as if I were a foreigner. God, I was born next door in Ohio! They mumble as if they did not understand how to not be loud Americans yet cannot modulate their voice to carry language carefully, as in a china tea cup full of words. Was I like that?

Smith gathers the department heads, the branch CEO and his nodding flock. The meeting room is polished as shiny as the space can bear. As if to overcome the yellow-slate cloud that they see clinging to his Armani. The people as well as everything within the building is dressed to look successful. To instill confidence. To overcome the numbers. To fool the eye.

They’re smiling and sucking up to me. I am their executioner and they can smell the pungent black scent of their own death. They sparkle for today alone, like fireworks they flew up in the air and now as cinders blow through the city wind. Float down the river. This is what I’ll leave behind.

It surprised him that the women didn’t cry. One man did. “What will I do?” he’d said, just before he burst into sobbing. No one looked at him except for John Smith. Smith smiled his most human empathetic smile. It wasn’t his fault, after all.

It went well. I’m supposed to fly home this evening. What went wrong? I told them it went well. Why me? What will I do?

He clicked off the phone and stood there looking out the window of his room. The city glowed with sunset then simmered into dusk. Before his eyes it melted and ran down like candlewax into the streets. Cars left in the middle of the road were dissolving into soup. People were screaming and standing still, afraid to run. The floor beneath him shuddered, softened into tar.

What will I do?

*****

#44 INDEPENDENCE DAY

“About a dozen kids so far.”

“Ours?”

“Fault? Well maybe, since we imported the stuff and distributed all over the U.S.”

“Well we didn’t import it, Chaffee did, right?”

“Yeah, Chaffee, but we let it get in. Our inspectors gave it the U.S. seal of approval.”

“Fuck. Why?”

“Because it helped fill the quota from China that we’re required by the trade agreement to take in.”

“So you think the inspectors were a bit blind?”

“Of course. Same thing on the toys and the cars.”

“We’ll have to take some of the heat off China or we’re in deep shit. We’ll blame Chaffee. They’re a large corporation, right? Worth billions?”

“Yeah.”

“The public will eat that right up.”

“Yeah.”

“And the kids?”

“All Chinese so far.”

“Good.”

*****

#43 THE SOUND OF AQUA SKIES AND CHAMOMILE TEA

I caught a drift of chamomile. That odd yet natural smell that exists without words. Its lure beyond its herbal remedy wrapped up in its scent. Twisted in reminiscence is the forgetting that I never liked the taste. Its aroma promises a ridiculously delicious flavor and so I bought the tea. Tea that sat and dried out in my cabinet. One bag missing, one cup spilled down the drain. But memory persists within this scent of her favorite night time tea, of the same-scented shampoo, of her. Now I often steep but never drink it.

The early evening is a paint-by-numbers filled with impossible colors of aqua and coral that layer with streaks of clouds. She would have sat out on the back deck painting it, the colors settling into the canvas even as they blend into the horizon of trees. I would have come out with a shawl to protect her from the chill, stood there watching as the colors faded darkly into night.

The early evening is a paint-by-numbers filled with impossible colors of aqua and coral that layer with streaks of clouds. She would have sat out on the back deck painting it, the colors settling into the canvas even as they blend into the horizon of trees. I would have come out with a shawl to protect her from the chill, stood there watching as the colors faded darkly into night.

My name is Jeremiah and by the pale lemon wash of a full moon night I can see the sticky track of ants left by a day of hunt and plunder. No, I am not dead nor hold onto psychological propensities for the dramatic or the insane. I am just near-dead. I am a man who feels too much and yet feels nothing.

Still torn between the understanding and the incomprehensible; the mystery of life and the temptation of death. Smeared by years of apathy that shine like snail trails on my coat of rusting armor. I cannot help it any longer though, I need to grasp the story unfolding all around us and in doing so, find the paths that lead to rooms and countries full of screaming, hurting, people. And why she had to die for them.

I write poetry. I stretch deep inside and scrape the walls and yet the blood beneath my fingernails is dry and dead before it can ink the words into reality. I read her letter yet again. This, the last one sent and dated before the blast of bomb that sent shrapnel and bits of army jeep into her heart. “Kiss the kids for me. All my love, Maria.” The bile of bitter anger rises up before I swallow it softly down again. She should have been here. Did she know, curled up in a ditch with nothing but the slim sliver of a crescent moon to write by, did she know this letter was her last? Did she know I’d get the news of her death before I read her goodbye? And yet I had a sense of it, of the imminence of her leaving.

I imagine a night black as a raven’s wing with feathers of fear nearby, caressing necks unwashed except by wind and sand. I imagine her scowling as she keeps her head down low, not understanding the why of this war completely. While I stayed home not understanding how anyone could shoot at her; this woman, my wife, who has a tiny mole on her thigh and breasts like ripe peaches. I cannot comprehend this too: how she could have left us because she thought she should protect a stranger’s family instead.

Tonight I hear the rumbles of a storm and imagine it to be the distant bombs. I close my eyes against the clouds that sneak up on the moon and clear my mind to listen. She should be hearing me, reaching back with one last touch. She should and yet I cannot feel it. Cannot, even with my poet’s mind, pretend. Perhaps it is too soon or maybe just too late beyond the time she’s given. Instead I hear the thunder and imagine in this charge-filled night of far-off lightning, the fear of every night filled with flash and smoke. I shudder.

I hear a cry, small and pitiful. I strain to hear her. It comes again. I turn around to see our frightened four year-old come shuffling through the shadows of the darkened room. I hurry off the deck into the house to hold and comfort her because I can.

*****

#42 STALKER

(path)

His job is on the night shift. He is dropped off at dark and picked up before the first rays of dawn. It is lonely, though he does sometimes hear the steady sound of another worker off in the distance. It is an easy enough task he is dealt and he is good at it. He likes working out in the field. While it seems mundane and tiring, he feels he is part engineer and part mule. Mainly though, he is an artist. Jon is a cornwalker. Though sometimes he works in wheat or alfalfa, he is the acknowledged expert in corn.

“You’re just a stalker!” his wife Ella has said. He hated that term and he hated that he could not make her happy. He felt he was sensitive and creatively articulate, drawing intricate patterns that told stories. He’d come home and wait for her to wake up so he could point to Earth and show her through the telescope his night’s work. Of course, his nights ran seven days long and his seven day “nights” were only one night of Earth’s measured time. Earth was a fast planet, a mirrored disco ball spinning flashes of light and orbiting its sun like a teenager just getting his license. Jon wondered if he could be happy living like that. Then again, he wasn’t happy now.

He’d show Ella each of his new pieces through the telescope, knowing just about where on Earth’s surface he’d placed it. He knew latitudes and longitudes and light speed and the difference in rotations between the universes so he set the scope up before he left in case she wanted to watch him work. Each time he came home, she’d say that she had forgotten. Or the lens wasn’t adjusted so she could see. Or whatever, but Jon knew she just didn’t care. To her, he was only a stalker.

He had worked on tonight’s art for a long time. His last two designs were intricate, geometrical (“It looks like a pizzelle,” she had said) and structurally sound. But they had been easy, repetitious, so he had finished stomping them out in the cornstalks early and sat at the edge of the field pencilling in his design. He had mixed emotions; he was excited to try something so different, yet he knew that it held a personal message to his wife.

He had worked on tonight’s art for a long time. His last two designs were intricate, geometrical (“It looks like a pizzelle,” she had said) and structurally sound. But they had been easy, repetitious, so he had finished stomping them out in the cornstalks early and sat at the edge of the field pencilling in his design. He had mixed emotions; he was excited to try something so different, yet he knew that it held a personal message to his wife.

Before he left, he adjusted the telescope to the setting and screwed it in place so it would remain there forever. He kissed her and held her longer than usual, until she squirmed out of his arms. “What’s wrong?” she asked, but she was laughing in a way that felt like needles pricked into his ears. He started to tell her, in one last bit of hope, but she turned away with a “Bye!” thrown casually as a towel over her shoulder.

With his design held in front of him Jon walked in the corn. The crunching of the cornstalks was a new rhythm to him on this night. He started to sing as he worked, digging his heels in and twisting the dried leaves into emphasis, granting himself the creative freedom he hoped he’d find in this new world.

He wished he could see it. He wondered how Ella would see this last portrait of him that he left her.

*****

#41 ELIZABETH ON A GOOD DAY

(water)

She danced in the wash of the waves, avoiding their grip on her ankles, bare toes in sync with the rhythmic pull of the moon. Like applause they rolled in crashing claps to collapse on the shore, then faded back into the mass of the ocean leaving wet stains like tears on the sand. Elizabeth bowed deep in appreciation, her skirt held out in a fan of windblown sail.

From the windows he watched her. She disturbed his concentration on his work, skittering like a mouse along the edge of awareness, burrowing in like the needs of a child to be seen, praised, protected. Whatever he could give, he tried to give her but she always clamored for more. Never asking, just letting him into that instant in her eyes, like a glimpse inside Pandora’s box, then closing herself against the reach of his words.

She turned her head to whip the hair back from where the wind had painted it on her face. She saw Robert watching, laughed and waved. He smiled as wide as his mouth could make it as if the space between him standing at the window and her windblown figure on the beach would diminish it as it traveled the distance. He waved the same way, exaggerated, with a pendulum sweep of his hand. He waved even as she turned back to the water, the wet foam slipping up and around each sun-browned bare foot, splashing and sliding back to the ocean.

Elizabeth sucked in her cheeks between her teeth, bit down hard just to feel how it hurt. She drew in a deep breath of the salt air, imagined it rushing down her throat, filling her lungs, splashing back as she exhaled. She took a step further into the incoming tide as it dragged at her feet, now reaching foam fingers cold and wet on her calves.

Robert watched for a moment more. She looked fine. She looked happy. Elizabeth had a love of the ocean that went beyond what he could understand. It filled the empty spaces he missed and he was grateful. He was glad they’d decided to come out here for the summer. She was safe here. He could relax. He sat back down and opened the laptop, waded through words, clung to numbers.

Before she walked into the ocean, she turned around one more time. She saw what looked like a shadow of him sitting. She wasn’t sure, it didn’t move, it wasn’t watching. She was disappointed because she had wanted to wave goodbye.

(First Publication Rights belong to The Fox Chase Review, Winter/Spring 2011)

*****

The Lost Children: A Charity Anthology

The Lost Children: A Charity Anthology